This is Sitting Queerly, a newsletter focused on the late blooming queer experience, the lofty goal of opening up conversations and celebrating those who embrace their full selves.

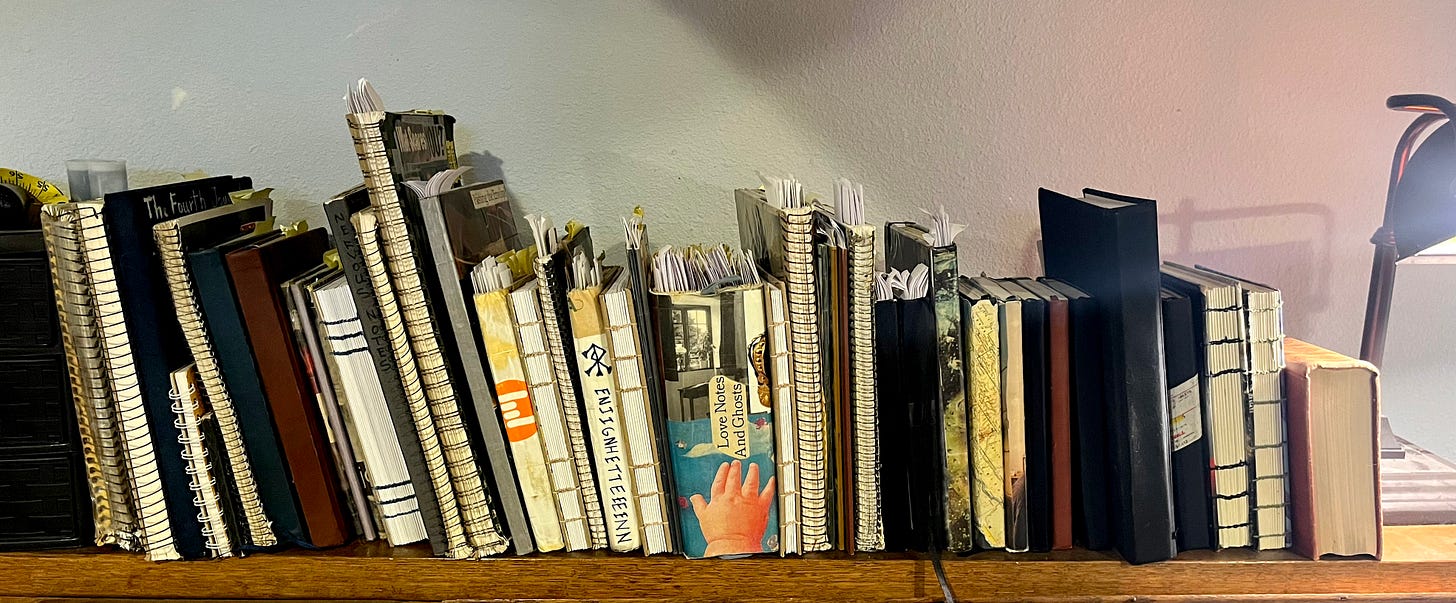

I have written before of my propensity to journal.

Twenty-eight years of my life are in these notebooks. Two-thirds of my life. And they aren’t just journals—they are commonplace books, art journals, sketchbooks, record books. Many of them are padded with countless clippings, plane tickets, movie tickets, photos and whatever other paraphernalia I deemed relevant for preservation.

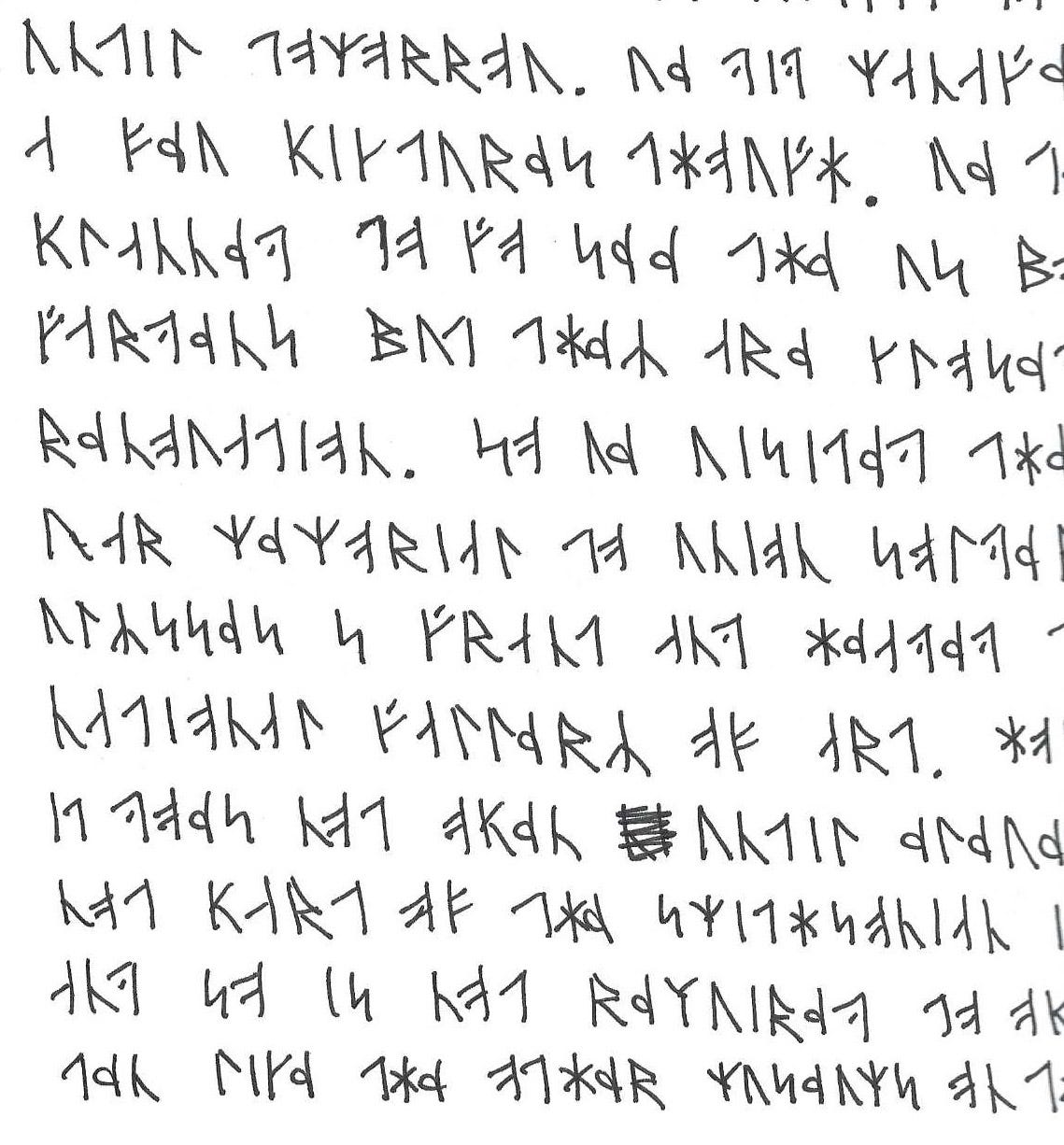

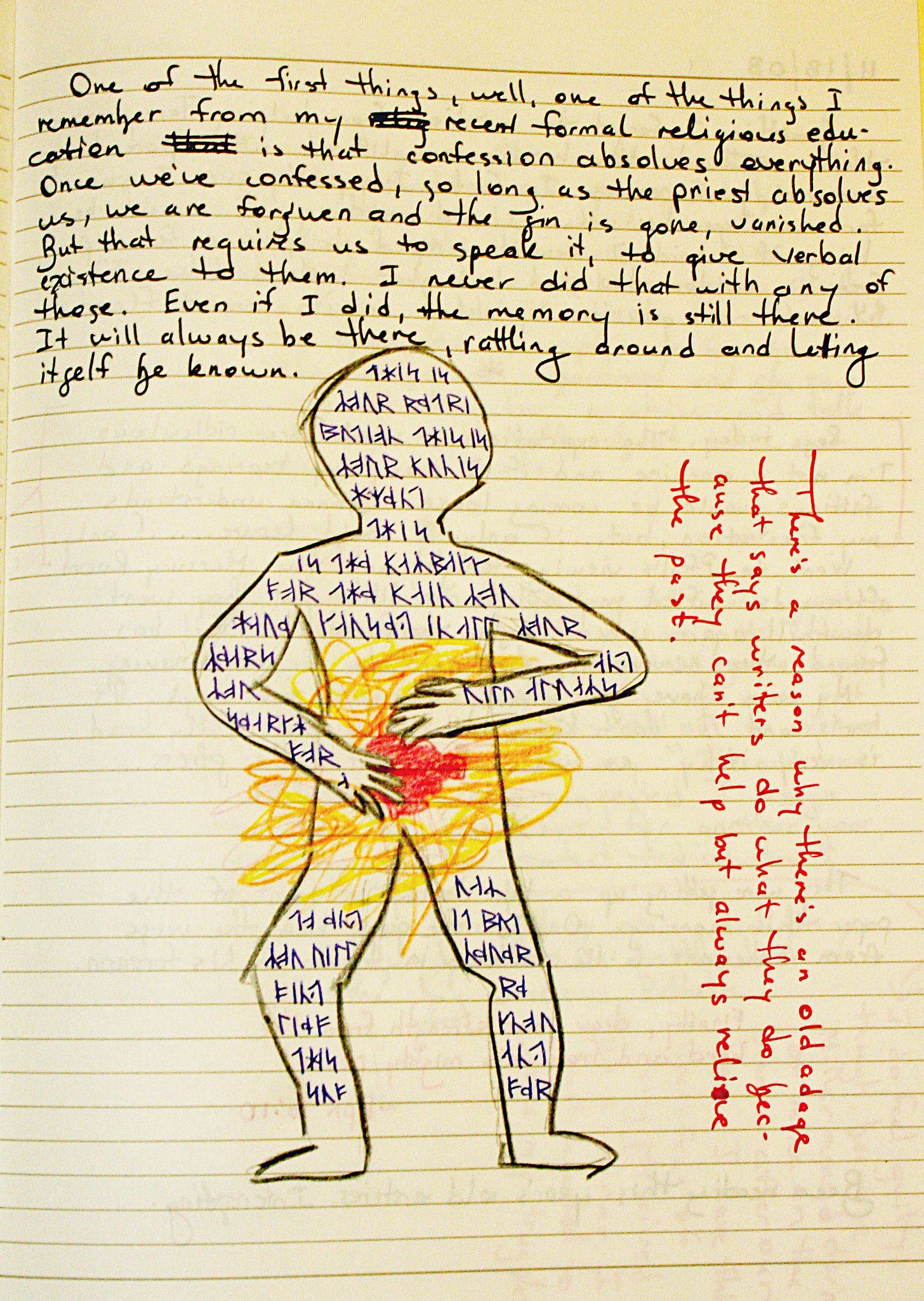

As far as I know, no one has tried to read them surreptitiously, though that’s something I was terrified of when I was a teenager. I was so scared of it, even of someone potentially glancing at a page as I wrote, that I began to write some things in code.

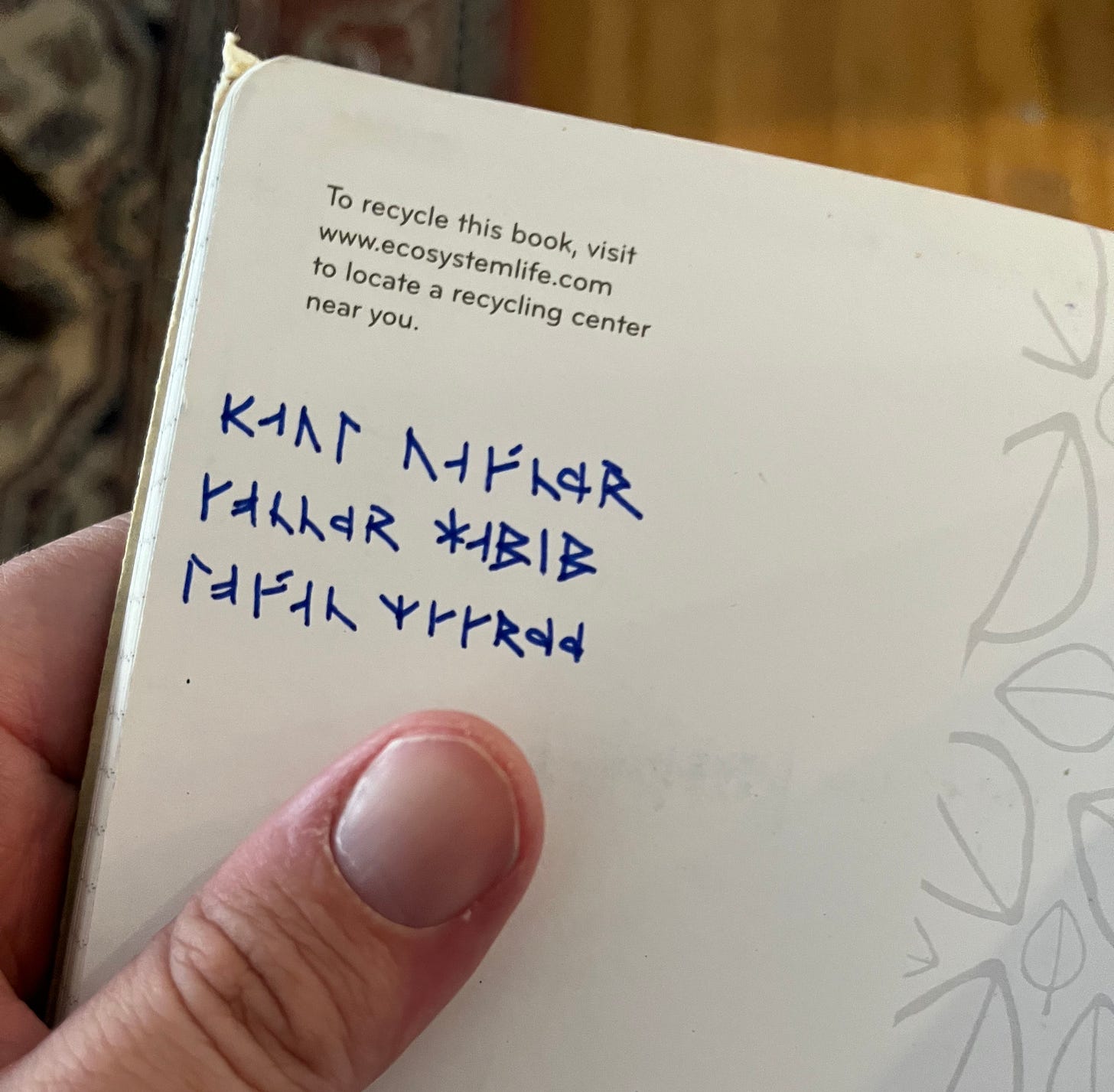

I don’t write at length in code; I can’t keep my train of thought if I can’t easily look back at what was just written. The code itself isn’t anything inventive; just a simple runic cipher I cribbed from an Eyewitness Book on magic back in middle school. Something just strange enough to not be immediately decipherable.

It is sufficient for me to write short blurbs or bulleted lists when dealing with topics I consider sensitive, inflammatory or explicit. Or, more appropriately, embarrassing. Anger at family members/friends/coworkers. Particularly dark thoughts associated with my depression/anxiety. And, eventually, realizations of and struggles with my queerness.

Any of the queer sex dreams I had, guys I encountered who I became attracted to, the guilt and shame I felt about all that, went down in code. I watched gay porn regularly enough beginning in college that I definitely had my preferred performers. Among others, Colby Jansen, Conner Habib, Paul Wagner. But I didn’t dare save links or videos to my computer, lest someone find them. So, to ensure I remembered who to look for whenever I jumped online, I wrote their names in my journal, in code.

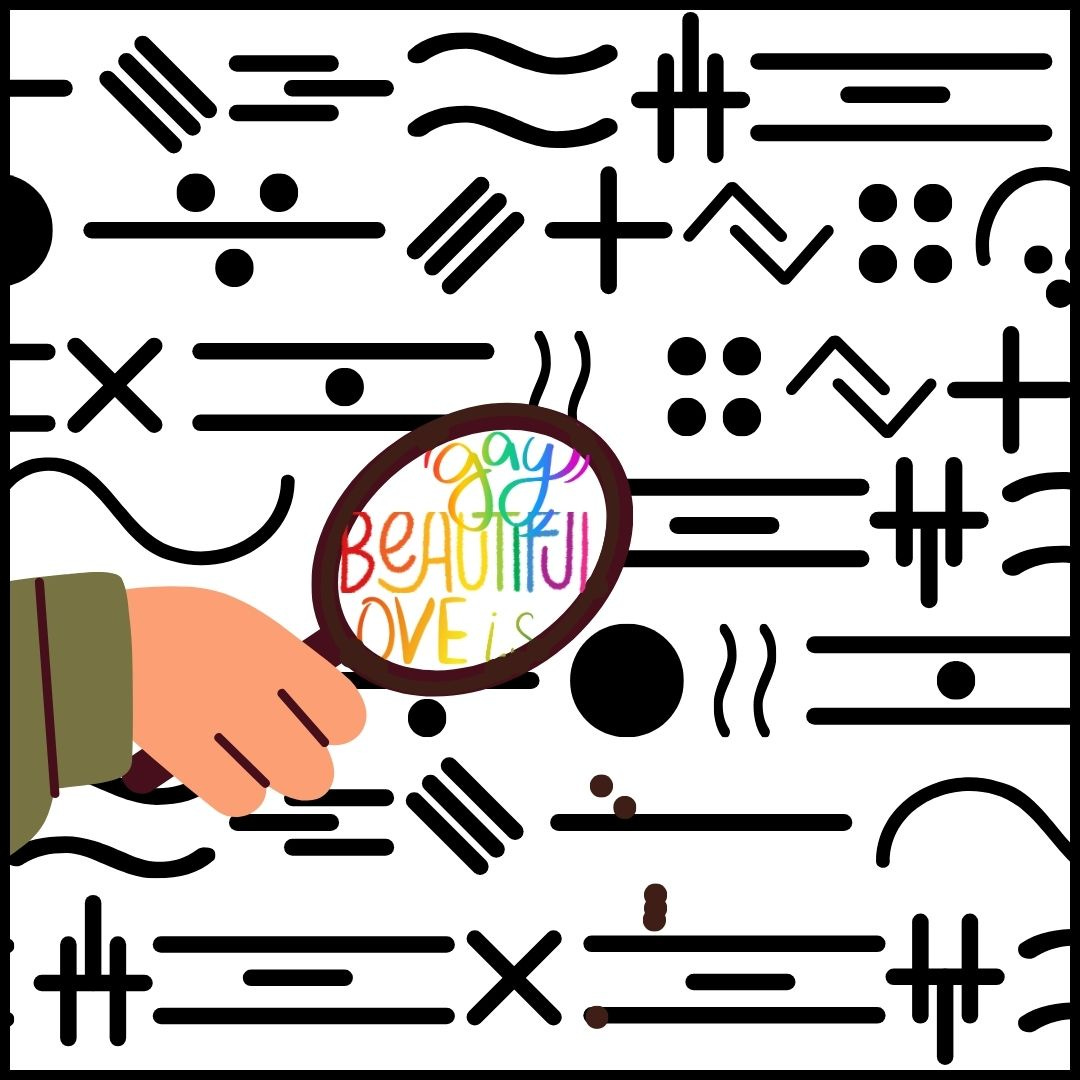

Codes loom large in queer history and culture.

There are examples of suspected and known queer folk obscuring homoerotic references in their private writings, such as Walt Whitman using number code to reference a man he’s alleged to have had a long-standing intimate relationship with.

Alfred Kinsey, the infamous sexologist, used a code he developed earlier in his career while studying gall wasps to record the sex lives of hundreds of his students and other individuals he interviewed.

More sordidly, the hanky code or flagging was a hallmark of queer culture beginning in the 1950s. Photographer Hal Fischer documented that practice along with other elements of queer fashion and identity typing in Gay Semiotics in the mid-1970s. At the time, flagging was a discreet-though-still-open-secret means of non-verbally communicating while gay men cruised for sex. Fischer acknowledged as much when photography magazine Aperture revisited the project in 2021:

[Interviewer]: How did you feel about decoding and making legible what was a subcultural language for a bigger audience? Did it raise questions for you about policing or surveillance, or how that translation might compromise the code?

Fischer: There was some criticism that I was exposing something with the signifiers, but it was minority criticism. I was myself, at that point, very critical of the gay photographers who were working in the city. I might be a little more charitable now.

Of course, all these things have something in common: the necessity for hiding queerness at a time when people learning someone was LGBTQIA2S+ could easily lead to that person’s ostracization at best and the loss of their job, family, freedom or life at worse.

Despite the clear and present dangers facing queer folk today in a highly polarized & fanaticized world, such culture-wide means to conceal one’s queerness are not in common use. Flagging isn’t actually practiced much for actual cruising anymore—we have apps for that—though has seen a revival in terms of fashion kitsch. Academic studies and surveys of behavior and other matters relevant to the queer community are administered all over the Internet, often providing the option of anonymity for participants.

In fact, today it’s seen as more noble and authentic to be upfront about one’s queerness, albeit knowing when and when not to shout it from the rooftops. And there are ways around that. Go on Etsy and you’ll find countless examples of discreet Pride accessories based on the various queer pride flag colors. Bracelets, rings, necklaces, T-shirt designs, stickers, patches. People who are in the queer community are likely to notice those subtle hints, perhaps reach out and help that individual build a network where they can be their full selves.

But hiding your queerness—staying in the closet, being on the down low, and so on—when it’s not entirely necessary is seen as everything ranging from a denial of one’s self on up to harm-enabling hypocrisy.

I like to think, I’m not embarrassed about my queerness, not anymore. While I’m not living fully out, I definitely don’t take pains to hide it anymore, based on the clothes I wear, the issues I talk and write about, the events I participate in.

And yet, when journaling, I still find myself putting some of my queer thoughts down in that runic script, set apart from whatever else I’ve written.

Because using that cipher isn’t just to stop others from reading what I write—it’s too keep me from easily reading it myself. To use a plot device from a book series written by an increasingly despicable TERFy children’s author, that runic cipher is like a pensieve where I could deposit thoughts and promptly move on from them.

I have begun easing out of obscuring my queer life in my journals, writing more openly and in plain language about my thoughts and feelings around my identity and how I’m expressing it or want to express it.

As they say, Rome wasn’t built in a day. And the same goes for shedding the habits we developed to hide ourselves when we shouldn’t have had to.

Coming in next week’s newsletter…

I try for the umpteenth time to recall and write about the events of the last time I played with my childhood best friend.

Master piece